During The Second World War, the U.S. armed forces began to fly large resource packages of food and other cargo to small islands in the Pacific. The US military shared some of the cargo — manufactured clothing, medicine, canned food, and tents — with the island’s residents. Many of the inhabitants of these islands had never encountered anyone from a developed country. They loved their sudden access to goods they had never even imagined.

When the war ended, the military forces left and the food drops stopped. The island’s native inhabitants wanted the food and cargo deliveries to resume. What did they do?

They imitated the visible structures that had accompanied the cargo. They built ornate airports and straw planes. They formed cults which worshiped nonspecific Americans having names like “John Frum” or “Tom Navy,” who they identified as the spiritual entity that would bring cargo to them again.

A straw plane built by the inhabitants of one of the islands

This seems irrational to us, but only because we have other models and knowledge of the world to explain how that cargo showed up.

Without consciously calling them to mind, we understand the basic ways that things work to make the cargo show up.

We know clothing and canned food doesn’t just fall out of the sky — there’s a whole supply chain that makes it. There is nothing intuitive about that though. It’s only because of our knowledge and life experience that we know the islanders’ techniques weren’t going to make the cargo come back.

If the only model you have for receiving cargo is that when a ground crew made up of guys with names like John Frum and Tom Navy wave their sticks next to a plane on the runway, then it is a reasonable and rational decision to build straw planes and imitate what you saw happening.

After similar monuments and rituals were discovered on a handful of islands, the phenomenon came to be called cargo culting. Cargo culting doesn’t just happen on isolated Pacific islands — it’s all around us.

Richard Feynman characterized much of what passes as science as cargo cult science. They imitate the visible structures of real science, including publication in scientific journals, but lack any basis in honest experimentation. It’s just going through the motions of science without engaging in the real rigor.

The term cargo cult programming describes software that contains elements which have been successfully used elsewhere but are completely unnecessary for the task at hand. A cargo cult programmer looks at the code used in some successful application and copies it to his own application, believing that the presence of the code will make his application useful.

Cargo cult entrepreneurs copy the tactics used by another successful startup or business without understanding the context of where they were used.

Cargo Cult Diversification

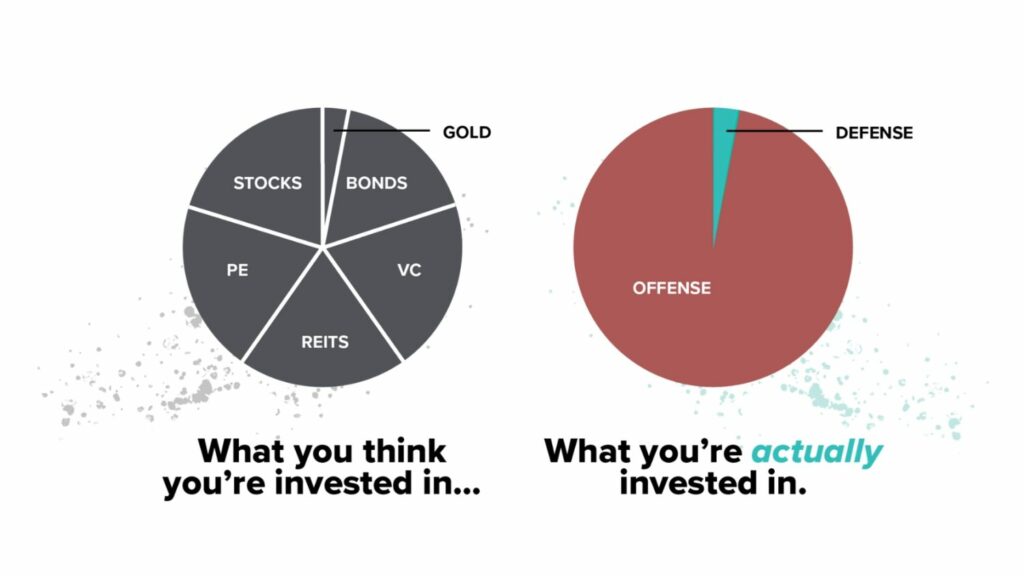

Cargo Culting exists in investing as well. Investors read about diversification and often build portfolios that look something like this.

On the surface, this seems like a well diversified portfolio of many different asset classes.

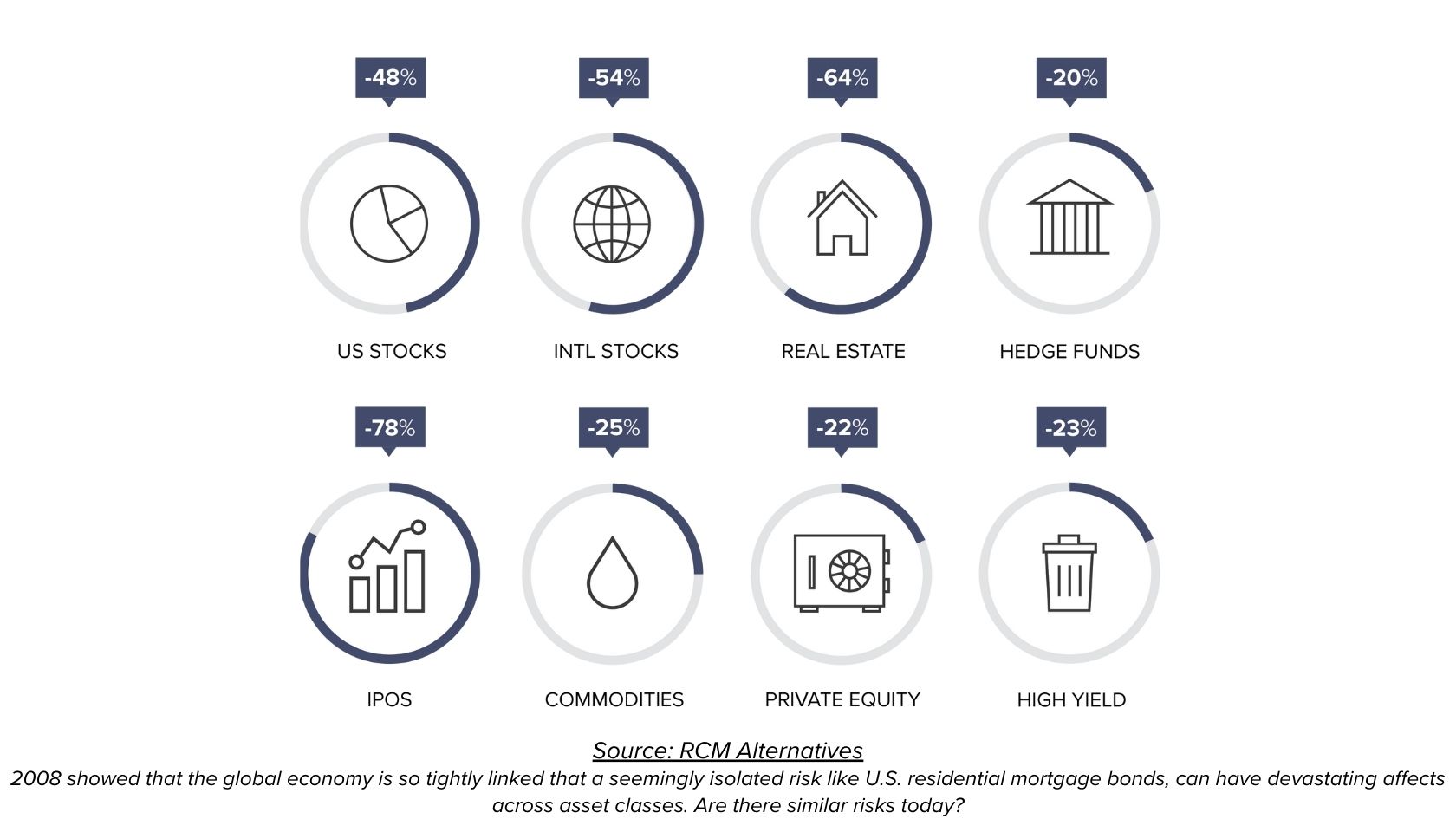

However, periods of real stress in markets such as the 2008 Global Financial Crisis can reveal that these diversified portfolios weren’t so diversified after all. They were actually all bets on the good times continuing.

Source: RCM Alternatives. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

Source: RCM Alternatives. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

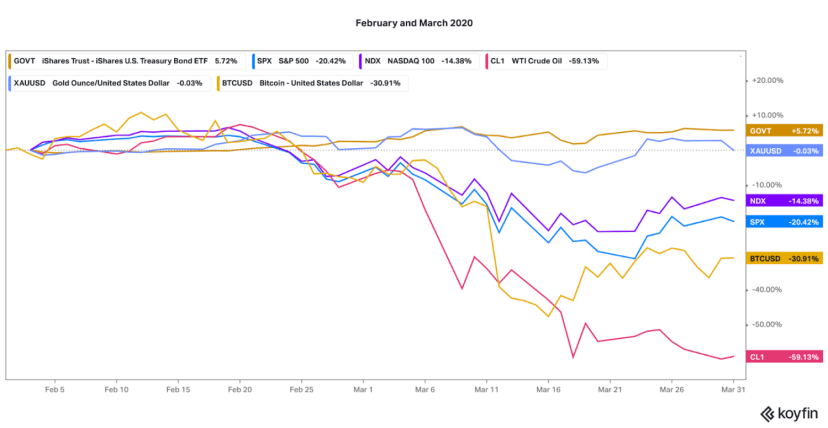

March of 2020 had similar characteristics where a diversified portfolio didn’t have anywhere to hide.

Source: Koyfin. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

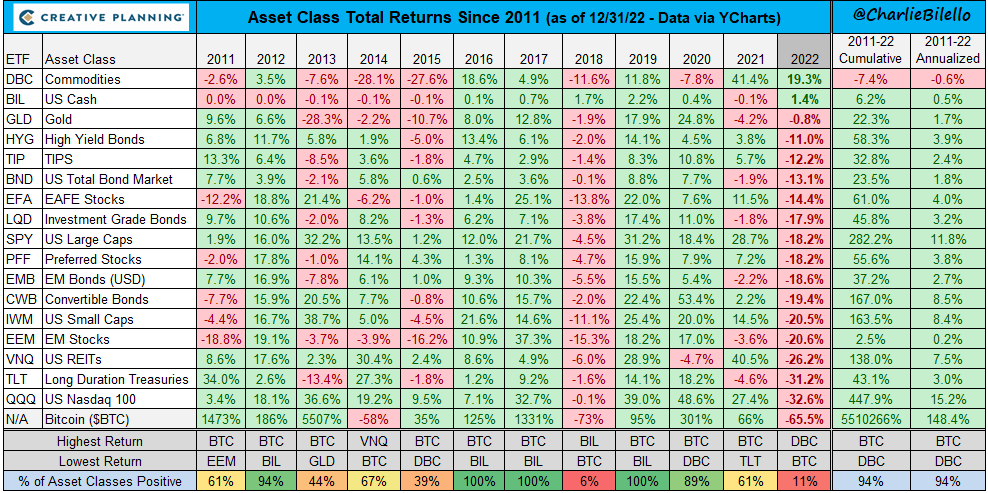

2022 was another year where there weren’t a whole lot of places to hide in traditional assets. As this chart looking at major asset classes showed, commodities were the only bright spot on the year. In our experience, a typical allocation to commodities in most investor portfolios may be in the 1-5% range. This is far too little to make a meaningful difference in the face of losses across the remaining 95-99% of the portfolio.

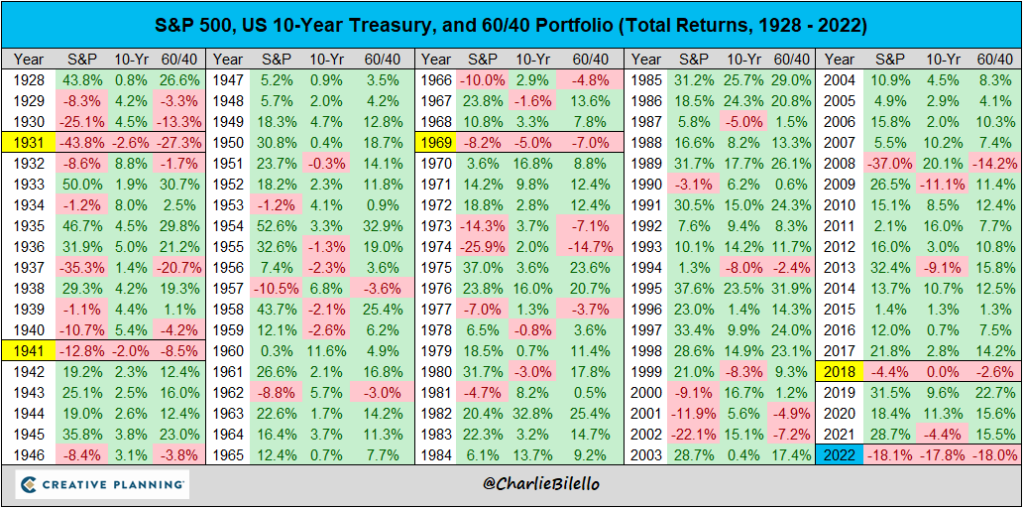

In particular, stock and bond focused portfolios struggled. 2022 marked the worst year since 1937 for the classic 60% stock/40% bond portfolio with a drawdown of -18%. Stocks meanwhile saw their worst annual return since the GFC in 2008 and 4th worst return in the past 70 years.

Source: Compound Advisors. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

Offense Wins Games, but Defense Wins Championships

We believe that all financial assets can be seen as either offensive or defensive and that the balance of offense and defense allows one to most effectively compound wealth through all economic cycles.

In our experience: most investors’ portfolios are almost all offense. We group any long GDP asset that benefits from economic growth into the offensive bucket. Stocks, bonds, real estate, private equity, and venture capital all fall into this category. These assets are typically correlated with stocks and broad economic growth.

They are assets that perform well most of the time, but when they perform badly, they can perform really badly as we’ve seen in prior crises.

A traditional stock and bond focused portfolio with some PE, VC, and Real Estate sprinkled around the edges has turned out not to be as diversified as many would have thought.

We consider these portfolios cargo cult diversification. Looked at on the surface, they seem diversified. They are going through the motions of diversification. But, when you really dig under the hood, they are all just bets on the good times continuing.

While these sorts of offensive assets all have their role in a portfolio, to compound wealth over the long run while minimizing drawdowns, we believe investors should combine offensive assets with defensive assets such as gold, long volatility, tail risk, and trend following.

They are assets that may not perform great most of the time, but they should be at their best when offensive assets are at their worst.

We have a simple investment philosophy: Offenses win games, but defense wins championships. Offense can work great in the short term for a single game or single game, but you need defense to win consistently in the long run. In the same way, we believe offensive assets can put up big gains in years like 2021, but need to be combined with defensive assets to most effectively compound wealth in the long run.

Why? Because it’s the addition of uncorrelated and negatively correlated defensive assets that make the most impact on risk-adjusted returns even though they don’t offer the highest returns.

The Three Little Zigs, Zogs, and Zags.

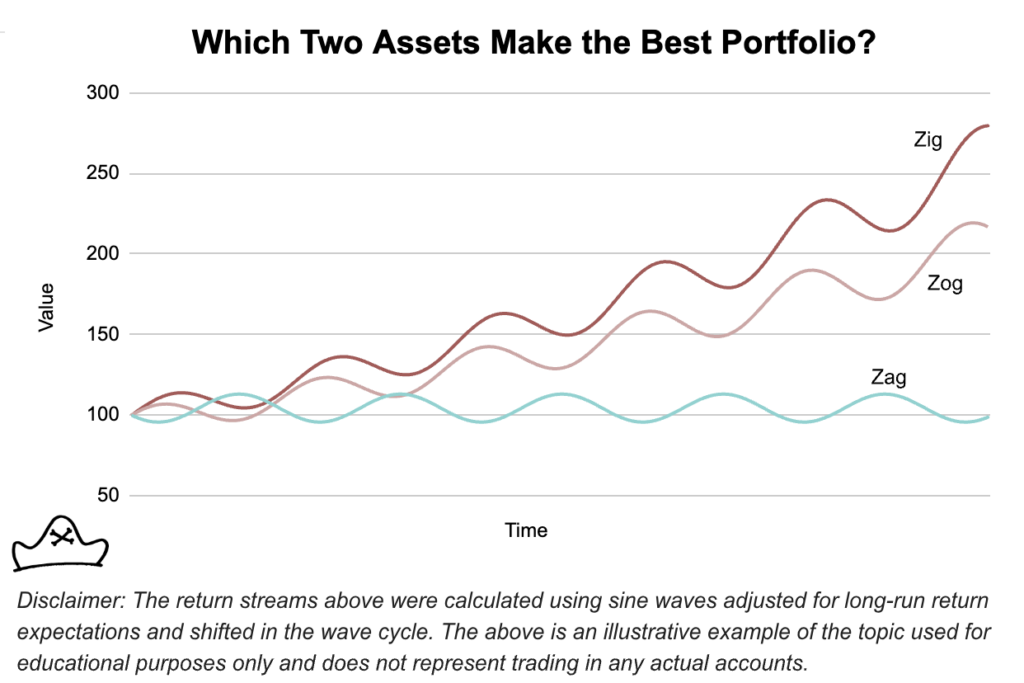

Let’s take a simple, toy example for illustrative purposes only. Let’s say you have the ability to buy two assets out of a possible three choices: Zig, Zog and Zag.

The first two assets, Zig and Zog have the highest returns so they seem like the obvious choices, right? Zag has a long run return of about zero so it seems like the least attractive option, right?

However, there’s one wrinkle here: Zig and Zog are highly correlated with one another. They track one another and the business cycle. Both do well when markets are up and poorly when markets are down.

Even though Zag has an expected return of zero, it goes up in periods where Zig and Zog go down. Its most substantial gains are when the other two assets are in crisis.

If you can only buy one asset, Zig is the obvious answer. It has the highest total return.

But, if you can buy two, what is the best overall portfolio?

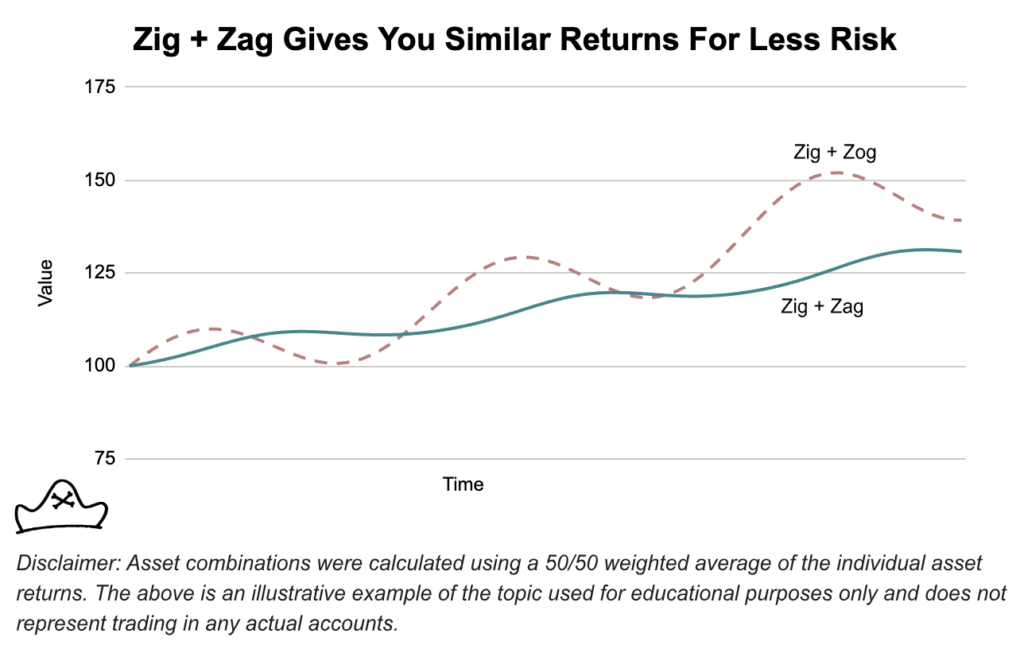

If you are rebalancing between the assets, the Zig+Zag portfolio gives you similar returns for less risk.1

Because Zag is negatively correlated to both Zig, a portfolio that rebalances between them creates a much smoother return stream – similar returns with much lower volatility and drawdowns.

This is a result of the power of anti-correlation and rebalancing. In periods where Zig is going up and Zag is going down, some of the profits from Zig are being rebalanced into Zag. At first glance, this seems weird – why would you sell the thing going up to buy the thing going down?

Because when the cycle turns and Zig starts to go down, Zag is more “fully funded” so that its gains will come at the best possible time. As Zig is falling, an investor with this portfolio would be able to buy more of Zig using the profits from Zag.

In other words, the anti-correlation of Zag is worth more to the excess risk-adjusted return of the portfolio than Zog’s superior expected value. Zag has the worst returns on a standalone basis. But, it provides returns at the right time to offset losses in the more offensive Zig.

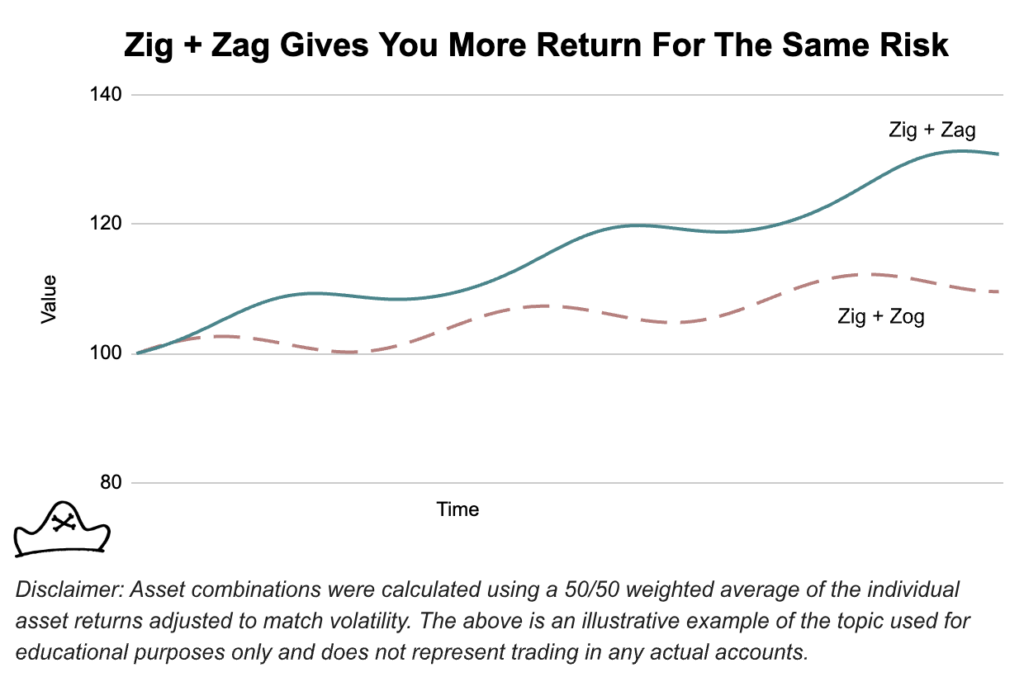

If you want to increase your risk-adjusted return, you are better off adding modest leverage to the balanced Zig+Zag portfolio rather than using a portfolio than the all offensive Zig+Zog.

By adjusting the Zig+Zag portfolio and Zig+Zog to the same risk level, Zig+Zag outperforms because of the power of anti-correlation and rebalancing. For any investor that cares about their risk-adjusted returns, Zig+Zag would be a better portfolio.

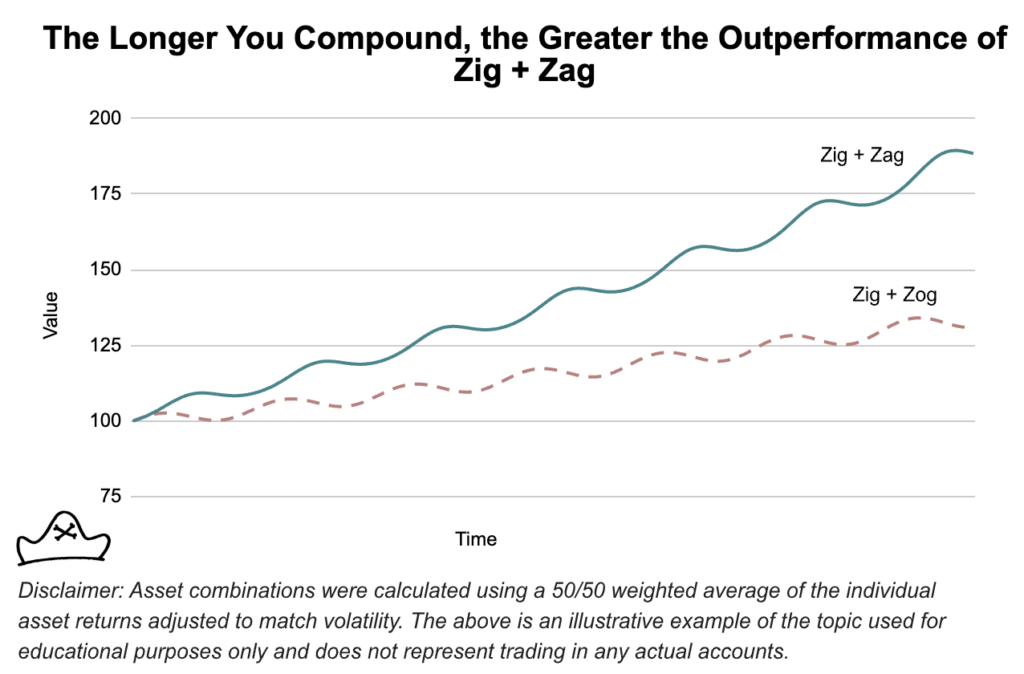

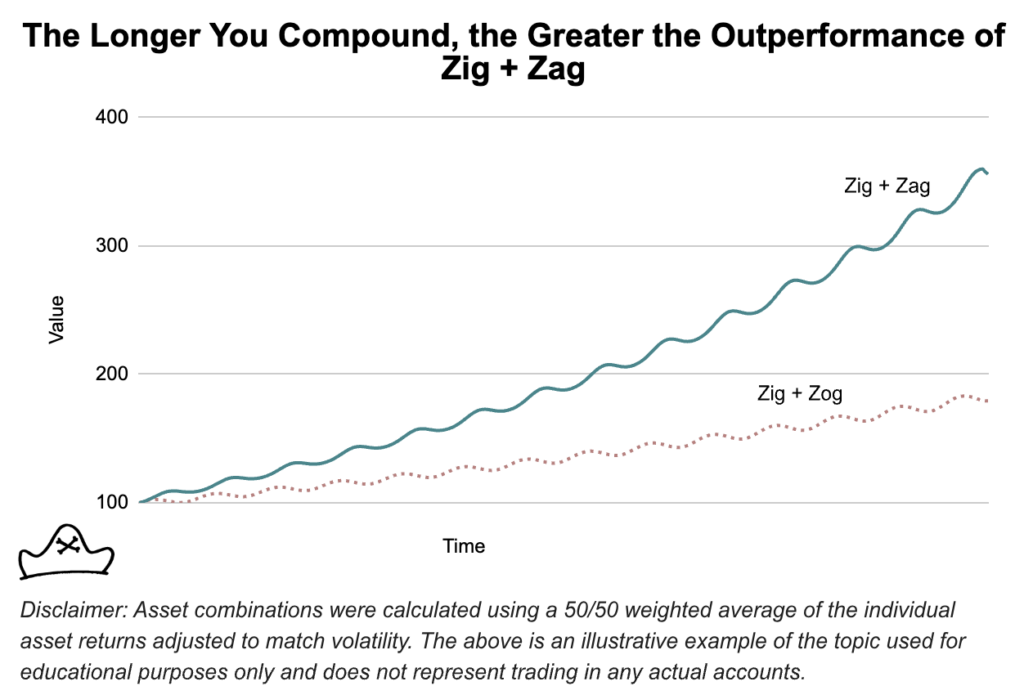

And as time goes on, it gets better and better.

And better…

As compounding takes its toll, what started as a small gap – turns into a chasm.

Portfolio Thinking

Most investors think about the expected value of a single asset. They say “I like this stock and that stock”. They look at each individual piece on its own: “which of these investments is going to do the best?”

Thinking about the portfolio holistically shows that you can add low returning but negatively correlated or uncorrelated individual assets to create a superior risk-adjusted return.

Using the principles of diversification, smart investors should be thinking “I should put some of my money in the investment that I think is going to do the best and then also put some in investments that I think won’t do as well but are uncorrelated or anti-correlated because if I rebalance between them, I improve the overall performance of the portfolio.”

Most investor portfolios today are concentrated in offensive assets like stocks, bonds, and real estate.

We believe that true diversification, the kind that achieves superior long-term risk-adjusted returns, requires making significant allocations to defensive assets. Everything else is cargo culting.

Footnotes

-

- Shown over the first 100 periods in this simulation.